Sometimes, the best ideas were there all along. They just need updating for today’s challenges.

By enhancing Mother Nature’s water filter, innovator Bill Lucas combined an idea to reuse drinking water treatment sludge in manufactured wetlands to remediate phosphorous at point and non-point water sources.

And along the way, he reached out to NRRI for expertise to improve the product’s physical properties and effectiveness. The resulting innovation is another example of University know-how providing tangible commercialization impact.

“Alum sludge” is a byproduct of drinking water treatment facilities, which is generally landfilled. But Lucas, doing research for his doctoral degree in 2007, knew that aluminum sludge naturally absorbs phosphorous since it has a positive charge and phosphate is negative. After filing for a patent in 2008, he had a patent on the filter idea by 2010.

In 2017, Lucas, with partners Mark Merkelbach and Jerome Ryan, formed Sustainable Water Infrastructure Group, or SWIG – an apt name for a process that cleans water.

In 2020, they approached NRRI with a critical problem: how to pelletize the fine sludge material into something more easily handled, durable and more effective in absorbing phosphorus, in a cost-effective way. NRRI engineers Cally Hunt and Matt Young also identified a proprietary biomaterial that, mixed with the recycled sludge, is showing promising test results.

“We identified an inexpensive commercial starch binder that would do the job well,” said Young. “We know binders from research over the years. And we mixed the media in different ratios, testing the performance until we had it right.”

Phosphorous problem

Phosphorus is a nutrient commonly found in agricultural fertilizers, manure and sewage or industrial discharges. Rain and snowmelt can wash fertilizers and manure off the land and into ditches, streams and lakes.

An overload of phosphorous in waterbodies leads to increased algae growth and harmful algal blooms, which are toxic and harmful to animals and people. Significant increases in algae harm water quality, food resources and habitats, and decreases the oxygen that fish and other aquatic life need to survive.

Old to New

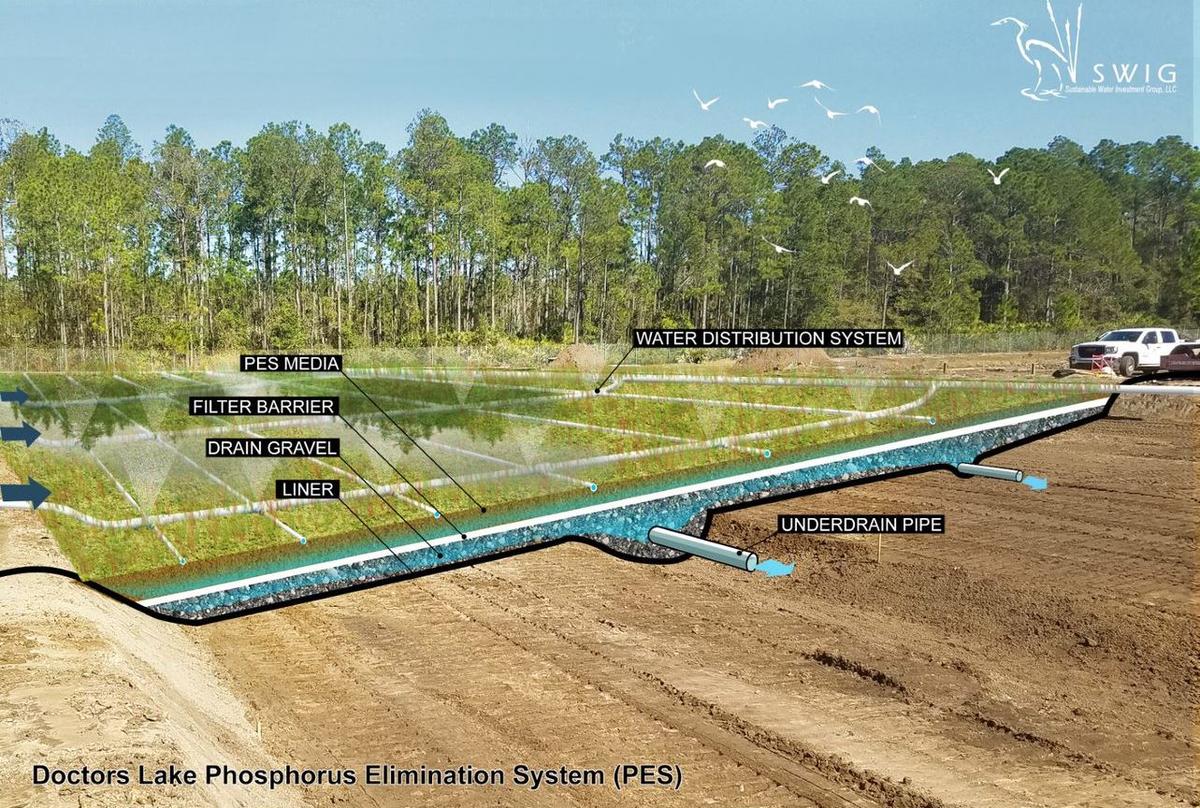

Borrowing from natural wetlands – nature’s water filters – the SWIG technology is a layered, vertical system with vegetation on top (which also absorbs some phosphorous), the specially mixed media (which absorbs 80 – 90 percent), a barrier and an underdrain pipe. Water is dispersed across the wetland then filters through the layers. Depending upon situation, the system is designed to last up to 15 – 20 years before the media needs replacing.

The systems are being deployed in Florida, working with two of the state’s five water management districts. Now with three successful demonstration projects underway, the company is getting attention from across the U.S. – from New Jersey to the Pacific Northwest.

“Florida has been leading on getting water quality projects off the ground,” explained Ryan, SWIG CEO. “Their economy is dependent on freshwater for development and tourism and their Basin Management Action plans call for all stakeholders to reduce the amount of pollution they’re allowed to discharge.”

Merkelbach, SWIG chief operations officer, added, “Florida is a bellwether of issues other states will see. I think we’re in an emerging market of infrastructure for water quality improvement and protection.”

NRRI & U Impact

NRRI’s role was instrumental in moving the SWIG proof-of-concept to an economical, market-ready process. SWIG is currently building a five-acre commercial processing facility in Lake County, Florida, on the basis of NRRI know-how.

“Their business model is to go into communities and provide phosphorous remediation solutions at a large scale,” said Tim White, NRRI director of Business Development. “But to do that, they need very economical materials. That’s where NRRI came in, to provide natural resource and materials know-how to make SWIG’s innovations commercially viable.”

According to Russ Straate, who helps inventors and entrepreneurs launch startup companies as director of the University’s Venture Center, it often takes a new company, like SWIG, to bring groundbreaking technology to market.

“But they often need to refine their technology significantly to attract investors or market interest,” said Straate. “This is a great example of commercial collaboration, and those of us on the University’s Technology Commercialization team look forward to working with SWIG, NRRI and future partners to help develop promising technologies.”