Whether you call them crawfish, crawdads or crayfish, one species of these small lobster-like crustaceans may be a problem for northern Minnesota wild rice.

The rusty crayfish is a prolific and aggressive species, native to the Ohio River basin. But over the past few decades, they’ve expanded their range into the Great Lakes region, most likely by anglers who use them for bait.

And like any of the 353 crayfish species in the U.S., “rusties” dine on aquatic vegetation. The problem is that once this particular species gets into a lake, their population explodes and they push out the native crayfish. Then the rusty crayfish chomp away. That adds one more threat out of many to Minnesota’s culturally and ecologically important wild rice.

“Our partners at the 1854 Treaty Authority performed some experiments by enclosing high densities of rusty crayfish with wild rice, and it reduced the vegetation growth,” said Brennan Pederson, NRRI senior lab technician and project manager. “So that confirmed that the rusties can tear up the roots and heavily graze on wild rice.”

So, how can lake managers and even lake property owners most effectively remove rusty crayfish once they’ve moved in? NRRI’s study set out to identify methods that are inexpensive, easy and effective. The team tested two different types of traps – baited and non-baited/refuge style – and several different types of bait.

Minnesota has some 30 lakes invaded with rusties, and the researchers picked three for the study that also host, or could potentially host, wild rice. The first field season was the summer of 2023. And the team learned a lot.

Muckity Muck

Wild rice grows best in soft lake substrates. But their traps sunk in the muck, blocking the crayfish’s entrance. After much brainstorming, the team came up with a sort of “snowshoe” solution – attaching simple bases to give the traps a bigger footprint on the muck.

“We developed modifications that are cheap and easy to assemble,” said Pederson. “Our goal is to provide everyone solutions to controlling rusty crayfish, from lake associations to the Department of Natural Resources.”

Research out of Europe indicates that the refuge traps – basically tubes with one open end that offer a safe hiding place – are more effective at attracting females. This is good because it’s those prolific females that provide the eggs and young. The baited traps are most effective at capturing males, but captures many more crayfish.

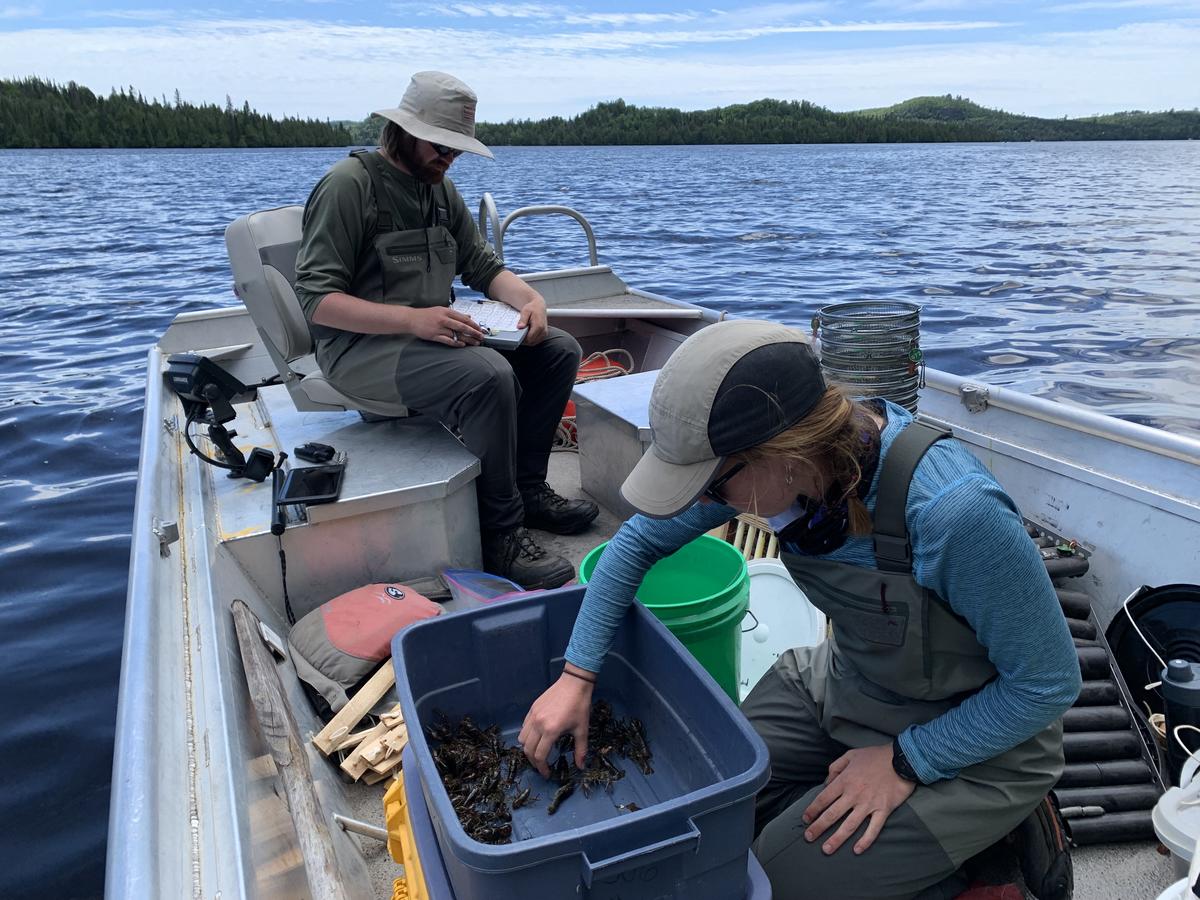

Gathering the Data

With the second year of field work underway this summer, the team is finding ways to work around the challenges of getting the data they need. A big one is aligning the field work with warm weather. And each of the three lakes are a couple of hours north.

“Crayfish are not active in cold water,” Pederson explained. “If we show up to a lake and the water is too cold, it’s very hard to catch crayfish and collect the data we need.”

The researchers want to know if larger baited traps will increase the catch rate or if bait choices and timing of trapping make a difference. They also want to understand how quickly rusty crayfish will move back into an area of the lake where they’ve been removed. The goal is to reduce the populations around sensitive vegetation, so knowing how far rusty crayfish will travel in a lake is important.

“This project has been a great opportunity to learn more about lake ecosystem function and aquatic invasive species,” said Pederson. “We’re also finding new questions to answer, like the implications of hybridized rusty crayfish with native species.”

PHOTO TOP: Project leader Brennan Pederson documents while technician Shelby Suhr checks size and sex of each caught crayfish.