When old man winter wallops the northland, keeping roads safe for drivers is a top priority for road maintenance crews. The challenge is using enough salt and sand to keep cars out of ditches, while minimizing its environmental impact.

Road salt – sodium chloride – is the most common tool in the road deicing toolbox. But along with its limitations, like not working when temps drop below 15 degrees F, it is also a harsh and permanent chemical when it reaches the freshwater environment. The salt washes into streams and lakes and keeps building up over time, harming both plants and animals.

“Duluth’s drinking water comes from Lake Superior, so we’re potentially polluting our own drinking water with all the salt we use in the winter,” explained Chanlan Chun, the lead NRRI researcher on two road salt projects. Her goal is to gain better understanding of the problem to lead to comprehensive solutions.

One project, funded by the Minnesota Dept. of Natural Resources, is researching when and where salt is getting into streams along the south shore of Lake Superior. The second project is funded by the Minnesota Dept. of Transportation to understand environmental impacts and comparative cost of potassium acetate applied as a salt alternative.

Salty streams?

Collecting data on chloride contamination in Duluth streams when they’re still iced over is a challenge for NRRI researcher Max Brubaker. He brings a spike and mallet to chisel out access, when necessary. Or breaks through the ice with his rubber boots. The good news is that this data is best gathered on sunny, melty days.

“This is just perfect,” said Max Brubaker, standing ankle deep in Duluth’s Tischer Creek. “I am really enjoying this job. I get time outdoors and time in the lab.”

At each of five sites on Kingsbury, Tischer and Amity creeks, Brubaker fills two bottles with water samples that go back to the lab for general water quality testing. Then he tests the stream’s conductivity level to get a sense of the chloride content, as well as stream temperature, pH and more. Within 10 minutes Brubaker and a student assistant are off to the next site. The same routine is followed on Skunk Creek in Two Harbors in partnership with Lake County Soil and Water Conservation District. The data compares chloride concentrations in areas where the stream flows in wooded environments to more urban settings – upstream to downstream – all the way to Lake Superior.

Understanding the source and concentrations will allow state agencies to develop effective control strategies in the most cost-effective way. This project is funded through 2021.

Hold the salt

A well-known ice melter, potassium acetate, is an attractive alternative for a number of reasons: it doesn’t corrode steel and concrete, it is biodegradable in the environment and it deices as low as minus-10 degrees F. And while it’s a more expensive product, it can potentially have a significant positive impact by reducing sodium chloride pollution. It’s also an organic food for microbes and biodegraders in natural systems.

But there’s still a lot we don’t know. What happens to potassium acetate as it enters stormwater systems and flows into streams and lakes? What’s the impact of the chemical on dissolved oxygen, which is important to plant and animal life? What is the overall cost-benefit of using potassium acetate instead of sodium chloride?

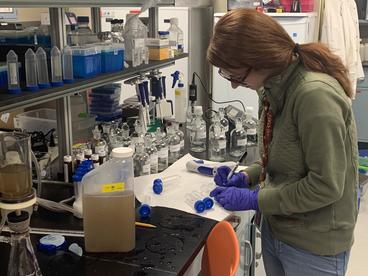

UMD graduate student Katie Cassidy, majoring in UMD’s Water Resources Science, is heading up the field work for this study. Throughout the winter, MnDOT applied potassium acetate on three stretches of Duluth roadways and Cassidy is collecting water samples from the stormwater catchment basins near the applications.

“In colder climates like Duluth, we really need to look at deicers that work in colder temps,” said Cassidy. “And if potassium acetate is easier on the environment, the extra cost might be worth it.”

The water is pumped up from the stormwater drains by an automated sampler, then collected and brought back to the NRRI lab for a suite of water chemistry analyses and to look for interactions with the potassium acetate. Cassidy also throws a bucket off the craggy shore of Lake Superior to pull up a water sample near where the stormwater drains. She examines concentrations and loads of road pollutants that are washing into the lake from the road.

This is the first year of the three year project in the collaboration with Dr. John Gulliver at St. Anthony Falls Laboratory. Potential future research could look at alternatives to sand for road grit, and identifying plants that tolerate sodium chloride for phytoremediation potential.