“The challenge – and the beauty – of field work is that it will take you to really remote places that you otherwise have no reason to go, and see things you wouldn’t otherwise see.”

NRRI aquatic research technician Bob Hell is a 20-year veteran of field work.

He knows that the summer field season also often means many nights on the road, is physically demanding, weather-dependent… and vitally important. It’s when scientists gather the real-world data to add to NRRI’s many environmental monitoring databases and on-going research projects.

Springtime signals preparation for getting out in the wetlands, on the water and deep in the forests.

“Field work also adds a lot of diversity to my job,” said Hell. “I’m not doing the same thing day after day, and it breaks up the seasons. I’m not sure I could handle a normal desk job.”

For the Birds

Since 1995, NRRI’s avian ecologists have braved the biting flies and ticks of Minnesota’s Superior and Chippewa National Forests to document the presence of breeding birds. Returning to the same spots year after year, they listen for the early morning calls of over 100 species of birds to understand population trends over time.

This information helps scientists and resource decision-makers better understand changes to the environment and make informed management decisions.

Other bird research involves improving habitat for young forest species such as the golden-winged warbler. And another seeks to understand the role of black ash wetlands and how to adapt management practices in the face of Emerald Ash Borer invasions.

Especially exciting for the field teams are new technologies – high quality cameras and better tracking tags – that allow them to gather more information, while keeping their distance from nests.

“Technologies and their applications have improved a lot over the years,” explained Avian Ecology Lab Leader Alexis Grinde, “They allow us to better understand different aspects of their ecology that we haven’t been able to document before, filling in important details.”

Neither Rain nor Heat… nor Tornado

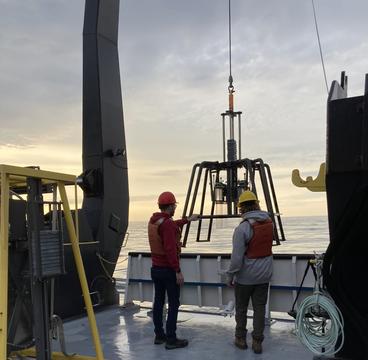

High winds, rain and thunderstorms can turn a routine trip to collect samples into quite an adventure on lakes and in streams. Of course, all equipment is thoroughly checked and fixed before crews get started. New equipment is onboarded and everyone is trained for emergency situations.

Preparedness – and good communication tools – certainly helped when a tornado approached a field crew working near Green Bay, Wisc., last year. The team leader in Duluth watched the radar and stayed in communication with the technicians so they had plenty of time to get off the water. They got to their lodging safely, but the next day had to saw their way through downed trees to get back to the site to retrieve their sampling nets.

Improvements in water research equipment over the decades are well appreciated by Hell and his research crews. Reaching some of the sampling locations requires long hikes through dense vegetation. Lighter electrofishing equipment – a tool used to capture, identify and measure fish in streams – is especially appreciated.

“Back in 2003, when I first started, our electrofishing equipment was gas powered with a generator, and it was heavy,” said Hell. “We looked like ghostbusters! Those were hard days.”

Other gear hauled out includes specialized nets to capture tiny macroinvertebrates in the water column and sediment and “Hess” samplers used in cobbly stream environments.

Help Wanted

NRRI hires large crews of college students to work as field technicians each spring. Hell and Grinde know what it takes to do well in a job like this – including getting dirty.

“A good field worker is a hard worker, observant and asks questions,” said Hell. “You have to endure long days, crappy weather and enjoy being outside. The technical stuff, we can teach.”

Avian field technicians are specially trained to identify birds by sight and sound, search for nests, and use radio-telemetry to track tagged birds throughout the summer.

“But what we can’t teach them is how to tolerate biting insects while working both independently and on a team,” said Grinde. “And truly, the key to a successful field season is having a good sense of humor.”

In the Lab

Samples and data collected throughout the summer are carefully stored for analysis later in the year and throughout the winter. And come spring, the process starts over again. Each year there are over a dozen simultaneous projects underway requiring field data gathering.

“Summer is all about the field work, going out and collecting samples and nothing gets processed until the off season,” said Hell. “So the stacks of gathered data sheets and hundreds of bottles of samples wait until October.”