Yes, it’s a cliche, but it’s true: There is no life without water.

That’s why understanding the complexities of water ecosystems – and how to protect them – is at the heart of NRRI’s Central Analytical Lab.

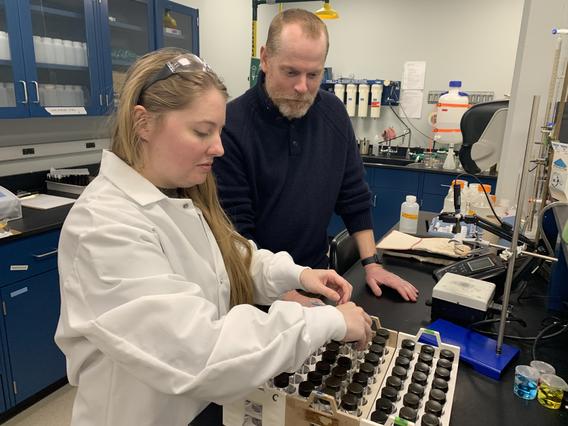

They’re a small but mighty team of five experienced researchers and two graduate students – gratefully aided by several undergraduate students each year. At any given time, the team juggles a dozen or more research projects and service contracts to inform the understanding and management of Minnesota’s water resources.

“We are all passionate about interacting responsibly with the natural world and studying it,” said graduate student Peter Birschbach. “This fuels our drive to work hard, pay attention to detail, and always give our best effort. Plus, we all love what we do.”

The passion is good, but the team’s experience and knowledge is critical. The Central Analytical Lab is a scientific resource for the entire state, and as such, is certified for water quality analyses by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. They follow strict protocols and quality control laboratory operations, from sample collection to sample processing and analyses.

“Natural resources agencies and clients come to us for water testing because they know we consistently provide defensible data,” said Lab Manager Beth Bernhardt. “We strictly follow the requirements of the U.S. EPA’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System and Minnesota’s State Disposal System to protect and improve the state’s water quality.”

And the lab expertise is deep and wide. Senior Researcher Jerry Henneck has been studying lakes and streams – especially focused on northeastern Minnesota – for some 30 years. That continuity and institutional memory provides an intimate understanding of how these lakes and streams function and have changed through time. This allows researchers to assess current water quality conditions with a historical perspective, which adds rich context.

Lab Director and Applied Limnologist Chris Filstrup also leans on the team’s varied backgrounds and skill sets in biology, chemistry, geology, sensor fabrication and deployment, and statistical analyses. The varied skills of the team, working with partners across the University system, provide an important holistic understanding of how lakes and streams function in their unique landscapes.

“We’re very collaborative,” he said. “Our scientists are just as comfortable supporting NRRI initiatives and research projects of our colleagues as leading our own projects on how regional lakes and streams respond to multiple environmental stressors.”

Water quality monitoring is a mainstay of the lab. From spring through fall, water samples come in weekly from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, Department of Natural Resources, and tribal resource managers for analysis. Winter is also busy, as the lab has developed a unique skill set in under ice research to understand how important this season is to water quality, and how loss of winter will affect lakes and streams.

“In addition to providing water quality results, we’re able to provide smaller organizations, like lake associations and homeowners, with interpretation of what the results mean and potential implications for the health of the lakes or streams,” said Filstrup.

NRRI’s own projects to study peatland restoration efforts at the Fens Complex near Toivola, Minn., and the expansive Great Lakes Sediment Surveillance Program also keeps the team busy. And a new study, funded by the National Science Foundation, is underway to better understand the impact of wildfires on lakes.

“While it might seem obvious that burned vegetation and charred soils from wildfires would lead to increased erosion into the lakes, it’s not clear how the water quality and organisms in the lake are affected by these disturbances,” said Filstrup.

Especially important are the long-term monitoring datasets – 30-plus years – that can be used to identify how lakes are changing through time in response to climate and land use changes, and ultimately what characteristics make lakes sensitive or resilient.

“If an agency has limited financial resources to protect water bodies, this information can help them prioritize the most sensitive lakes for protective measures,” added Filstrup, who thinks it’s the lab’s combined field and laboratory expertise that provides clients with more robust results and a holistic way of thinking about how aquatic ecosystems work

“Our deep knowledge of lakes and streams in this region allows us to weed out suspect results,” Berhardt added. “Our team effort is our superpower.”

[Photo Top: Winter water sampling February 27 in the St. Louis River Estuary for a NOAA-funded collaboration with the Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve.]