Zach Wagner works at the interface between water and land. But he’s not quite sure yet if he knows where that wide river of a setting may lead.

“I’m still trying to figure out my primary research interests,” he said. “So far, I’ve been the Water Group’s ‘shallow groundwater and water isotope’ person.” Quite a title.

Wagner came to NRRI in 2019 after finishing a master’s degree in Geological Science at UMD, working with Byron Steinman at the Large Lakes Observatory. And it’s the variety of tasks and unique NRRI research that continues to hold his interest.

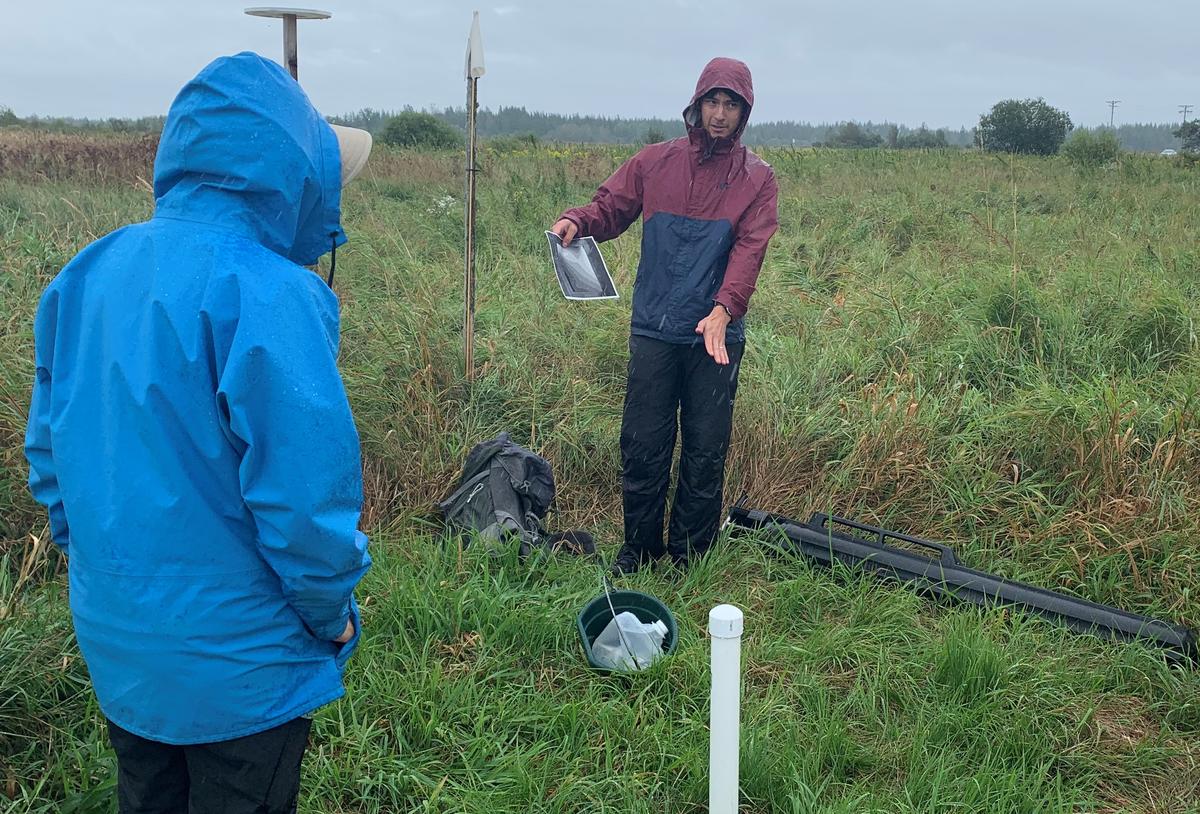

“I go from performing water chemistry analyses in the lab to pounding well casings into wetlands, or from surface water sampling in inland lakes and streams to designing wave drifters for measuring nearshore currents in Lake Superior,” said Wagner. “I like working across different disciplines involving freshwater.”

His skills are currently deployed on a project to measure the effectiveness of an ongoing restoration effort at NRRI’s Fens Complex, near Minnesota’s Sax Zim Bog. NRRI acquired the 425-acre site in 1986. The drained farmland was restored back into a functioning fen/bog peatland complex beginning in 2001, gaining valuable wetland credits.

“Peatlands, like NRRI’s Fens Complex, are important for nutrient cycling, carbon storage and wildlife habitat,” Wagner explained. “This project gives us perspectives on land use changes in an era where carbon credits and wetland credits can have big financial and ecological impacts in Minnesota.”

There are very few restored peatland sites of this age in the United States, which makes the new methodologies and knowledge gained especially important to other restoration efforts.

Continuous Collaboration

Wagner and his colleagues in NRRI’s Water Research Group collaborate across the institute and the University system to get the diversity of expertise and equipment needed for each project. The Fens project relies on the Data Collection and Delivery group to help manage projects with decades-long datasets.

In addition to hydraulic and water chemistry data, mammal, bird and insect data are also being incorporated into a report on the restoration effectiveness. The hydrology is important since peatlands need specific water levels just to even stay peatlands. Staving off invasive plants to allow the return of native vegetation species and animals is also critical.

Gear for sampling water and measuring stream flow is regularly shared with UMD’s Swenson College of Science and Engineering. The Department of Bioproducts and Biosystems Engineering on the Twin Cities campus also helps with the water isotope analysis and interpretation.

“The Fens site has become a sandbox for testing what works in a tough environment,” said Wagner. “We are constantly dealing with big temperature changes, beaver interference and a ground surface that constantly moves.”

(Fun fact: Bogs “breathe!” The “land” surface moves as the peat soaks up water and then dries out again across the seasons.)

Central Support

Water sample collections are dropped off daily at NRRI Duluth for water quality analyses in the Central Analytical Lab. Wagner appreciates the help of NRRI’s front desk team to notify the lab so team members can process and analyze them.

“We had a busy summer with samples from government agencies working on the National Lakes Assessment which samples 130 lakes across Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan,” said Wagner. “And that’s in addition to the long-term monitoring samples we receive from tribal groups, the Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve and our own intensive sampling projects.”

Off Hours

One would think Wagner gets enough of the outdoors, spending many workdays in waders at the Fens Complex. But off hours are often spent cross country skiing, mountain biking and hiking.

“Anything that gets me and my little family out in nature,” he added.