The best part of science is discovery. And NRRI scientists made a big discovery about a tiny, single-cell algae.

This little enigma – neither plant nor animal – started showing up in Euan Reavie’s Great Lakes research with greater abundance in about 1980. Reavie is a NRRI paleolimnologist, studying how tiny Great Lakes algae have responded to water quality changes over the last 200 years.

So when he and his team stumbled upon this unknown species, they gave it a temporary name, “Cyclotella species #1” and moved on. But they went back to it because exact taxonomy – the classification of species – is really important to these scientists. And they got to name this one.

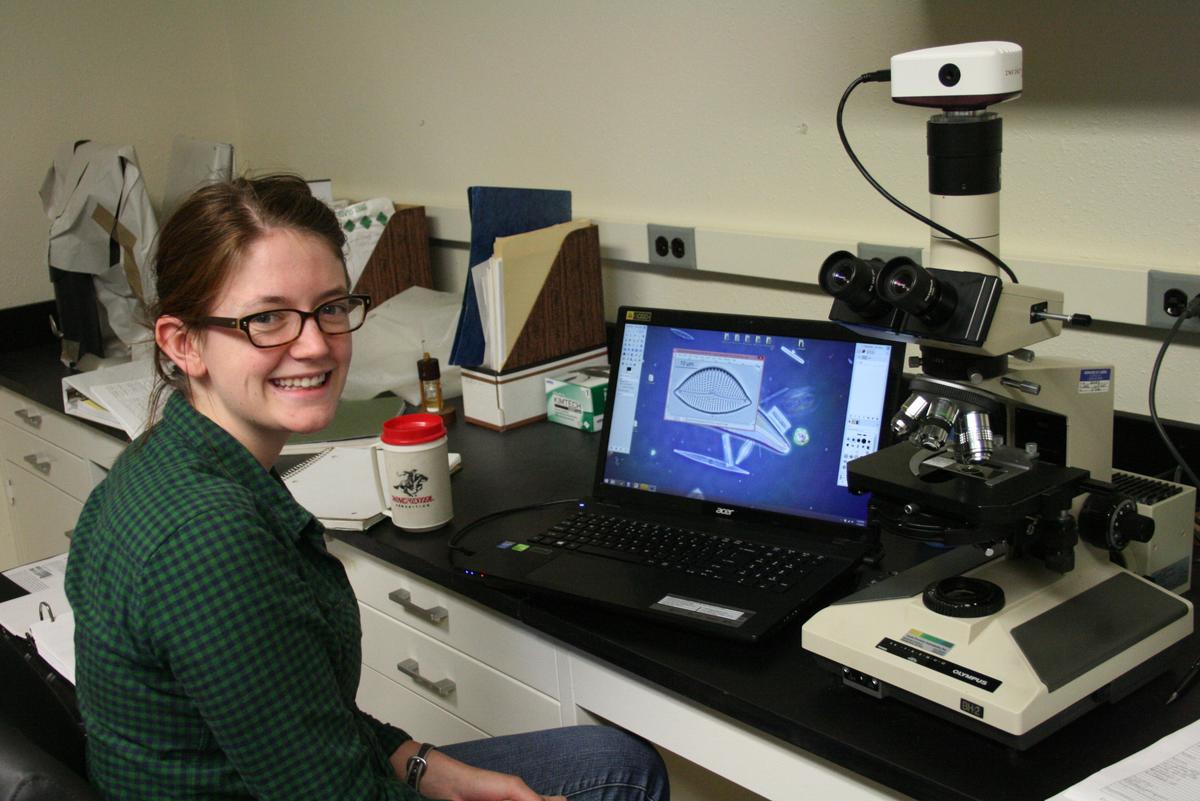

“Diatom algae are really good indicators of the health of the environment around them because they’re so specific,” explained Elizabeth Alexson, lead scientist on the paper they published in Diatom Research, Vol. 33, No. 3. “They’re very predictable and we know this species is more commonly found in higher temperature waters.”

With decades of diatom species records from the Great Lakes, Reavie and his team have related species to their optimal range of environmental parameters. And this newly classified species – Pantocsekiella laurentiana (so named because of its dominance in the Laurentian Great Lakes) – is clearly indicating a rise in air temperature and low nutrients. How that will affect the aquatic food chain is yet to be studied.

“This diatom is very common and exclusive to the Great Lakes, but likely has been misidentified for many, many years,” said Alexson. “Since we’re out on the Great Lakes every summer we can really see the patterns and consistencies in diatoms. It’s really exciting to correct the taxonomy and name a new species.”

About Paleolimnology

NRRI paleolimnologists extract long tubes of sediment from lakes to reconstruct historical changes in water quality over hundreds of years. The sediment, deposited slowly over 300 – 400 years, holds fossilized diatom algae. These diatoms are very sensitive to stressors like nutrient pollution, salinity loading and suspended sediments. The changes in the diatom species indicate changes in water quality. It is estimated that there are as many as 100,000 species of diatoms, although only about 8,000 species have been described.