It’s no small thing to name an epoch.

This geologic span of time must exhibit certain, distinctive characteristics. Officially, the world is still in the Halocene Epoch that started after the last Ice Age. That’s almost 12,000 years ago and likely today’s world would be unrecognizable to a hunter/gatherer of that era.

So, there’s an academic push to name an “Anthropocene Epoch” to describe this most recent period in Earth's history when human – anthropogenic – activity started to have a significant impact on the planet's climate and ecosystems.

“We are very close to having this separate geological epoch called Anthropocene, but it’s still under debate,” explained Michal Woszczyk, a visiting scientist at NRRI and Associate Professor from Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. “The term is commonly used to reflect human influences on the environment, but it’s not an official geological term. Yet.”

Woszczyk’s research is focused on whether or not PFAS – Per- and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances often called “forever chemicals” – can help define this new human-influenced epoch. And he came to NRRI to learn how to analyze for these compounds in sediments.

Technique and Technology

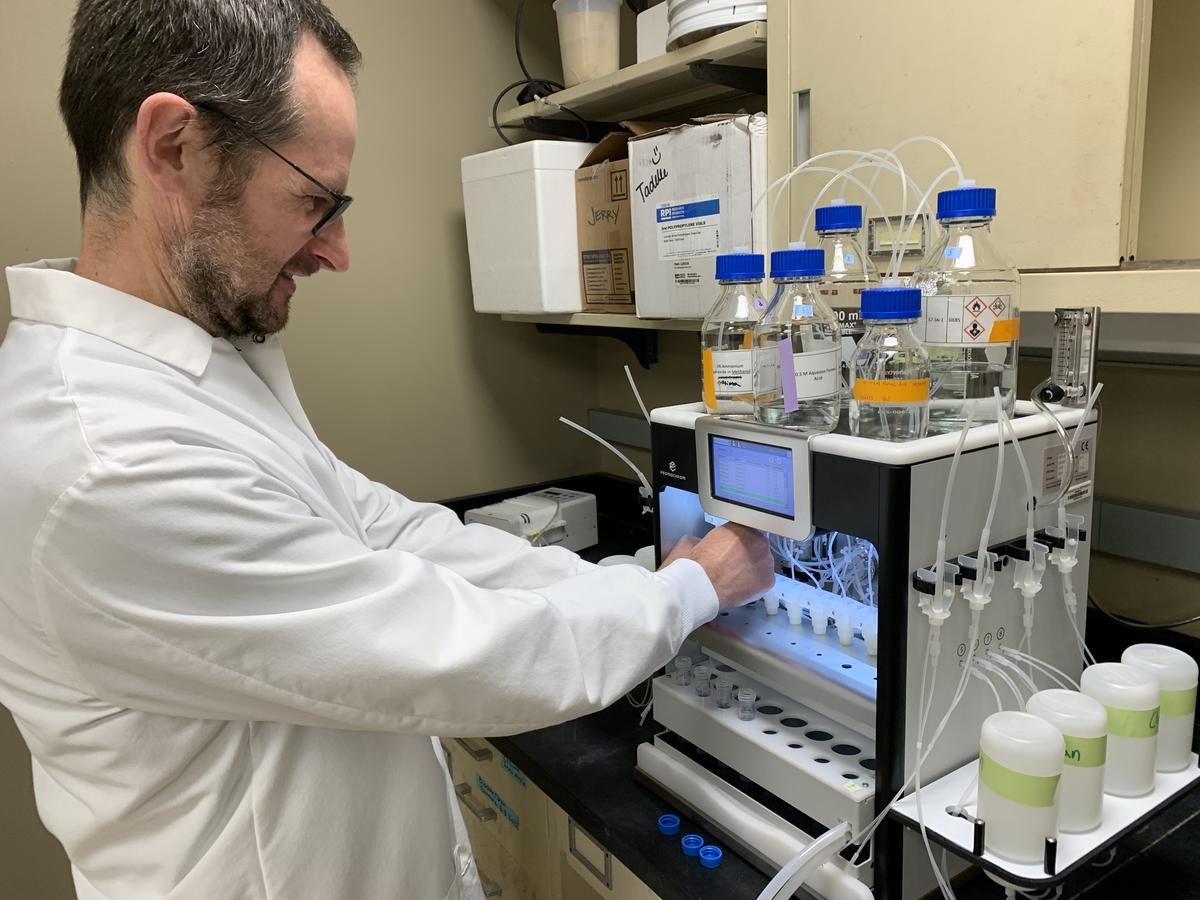

NRRI has onboarded unique expertise and infrastructure to detect PFAS– as well as hundreds of other chemicals – in sediment collected from lakes. This capability is integral to the Great Lakes Sediment Surveillance Program, led by a team of NRRI researchers, which aims to understand the presence and impact of legacy and emerging chemical contaminants in the Great Lakes. This program is funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Arriving in the winter of 2022 with 24 sediment samples from Lake Shalkar, KZ. in East Kazakhstan, Woszczyk was welcomed by Bridget Ulrich, NRRI Environmental Chemistry Laboratory Leader and PFAS expert.

“Standardized methods for analyzing PFAS are still evolving,” said Ulrich. “But we learned a lot working with Michal’s samples because they contained very high levels of organic material, making them particularly challenging to analyze.”

Epoch Marker?

To define the Anthropocene Epoch, scientists are identifying “markers” – unique indicators that could only be present during this era. Examples include microplastics, radioactive elements or biological changes. Woszcyzyk’s hypothesis is that because PFAS chemicals were widely used in products starting in the 1950s, and they are distributed through the air and water, that they could be a marker of the Anthropocene Epoch. His experiment is to study lake sediments deposited over the last two hundreds years to see when PFAS chemicals start to show up and if their accumulation in the lake followed their release patterns.

Lake Shalkar was an ideal place for Woszcyzyk to get his sediment samples. One, it is in a remote and relatively pristine area which shouldn’t have much direct human impact but it likely to receive the PFAS from a long-range transport. And two, it is close to a former nuclear testing site, which was the source of radionuclides used for a high-resolution dating. This is important because correlations between PFAS and established markers could support the relevance of PFAS as markers of the Anthropocene.

“So I thought, if we find things like PFAS in such a pristine place, it would tell us that even if humans are absent, we leave behind human influences on the environment,” said Woszcyzyk. “Maybe, if people realize the changes humans are making on our planet, they’ll think twice about their actions.”

Back to the Future

The sediment analyses done at NRRI worked well for Woszcyzyk’s basic research and he provided a global perspective to Ulrich’s research team.

“He sits in on our team meetings and offers perspectives and ideas that we might not think about,” said Ulrich. “I’m pretty passionate about international collaboration and the importance of establishing strong relationships. That’s why, when he reached out, I wanted to work to bring him here.”

Woszcyyk will finish up his analyses when he returns to Poland and, if PFAS proves to be a reliable marker of a new human-influenced epoch, he’ll write up his results for an academic journal. If not, he also has core samples from lakes in Pakistan and Poland and will continue with his experiments. He returned to Poland at the end of June. The trip abroad was funded by a fellowship from the Kościuszko Foundation.

“I wanted to come to the U.S. because there are many great scientists in the field of biogeochemistry,” he said. “It’s been a great fit, even though my research goes back hundreds of years and NRRI studies the here and now.”