Trees seem pretty tough. But like all sentinel species – from tiny algae to birds to moose – trees respond to changes in their environment, though on a very slow timeline.

So, as we anticipate an increasingly warmer climate, how will that impact Minnesota’s forests? How about the accompanying drier soils? Changes in wildlife? Rainfall intensity?

“For instance, in drier conditions, we know that oak trees will do better than aspen trees, and oak trees grow much more slowly,” said John Du Plissis, NRRI Forest and Land Group Manager. “What does that mean for birds and mammals? For our forest products industries? For people who love today’s forests?”

Questions like these are very complex. And yet, that’s what natural resource managers face as they plan for future forests that meet the needs of today and generations to come. What can we expect of our forests in the year 2100?

Decision Support Tool

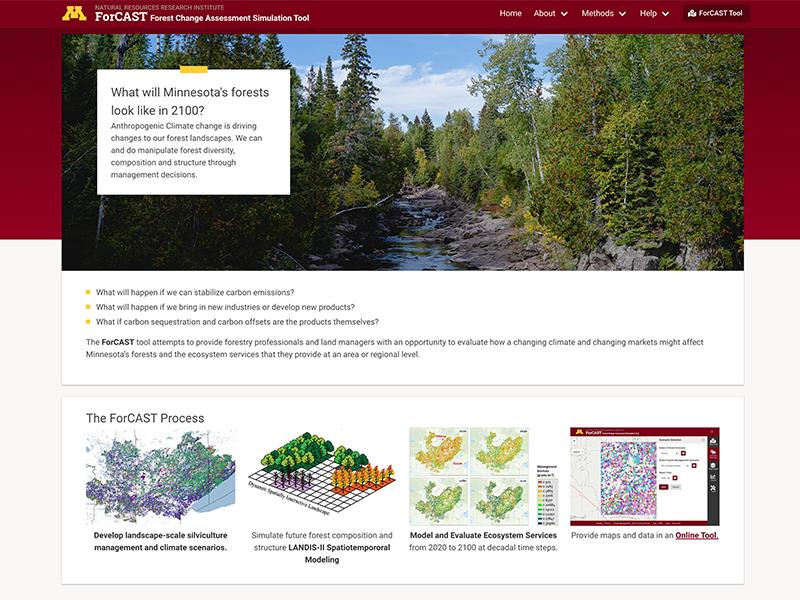

To help, NRRI developed the Forest Change Assessment Simulation Tool, or ForCAST. This unique, online decision tool integrates forest productivity, ecosystem services, and economic information to help land managers assess the potential costs, benefits, and tradeoffs between forest management options at a landscape scale over an 80-year planning period. It is a large, multi-disciplinary project, with funding provided by the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR).

“Things are changing; we know that,” said Du Plissis. “This tool helps us to envision what those changes look like and the investments we might want to make to maintain the things we value about and from Minnesota’s forests.”

This initial roll-out of ForCAST, launched in July, covers nearly four million acres in northern Minnesota – about 20 percent of the state’s forest cover -- spanning four major watersheds and encompassing private, public and tribal ownership. The watersheds are the St. Louis River, Cloquet River, Mississippi River-Grand Rapids and Lake Superior-South.

For Resource Managers

A ForCAST learning session will be held for potential users at the University of Minnesota Cloquet Forestry Center, 175 University Road, Cloquet, on September 29. For details and to register, view the Sustainable Forests Education Cooperative event page.

A resource manager can consider 12 scenarios for their selected area of interest. Among the scenarios, what happens if we increase wood harvest? Or decrease harvest? Or maintain current levels of harvest? What impacts will we see in water quality if harvesting declines t versus increasing harvests?? What changes in species can we expect if carbon emissions continue to increase?

Wildlife Impacts

Black bears, for example, are a common Minnesota forest dweller relying on berries, nuts and acorns for forage. NRRI Wildife Biologist, Ron Moen, found that effects of forest harvest vary in ForCAST modeled scenarios. Bears find acorns in older oak stands, and find berries and nuts in younger stands. When forest harvest levels were maintained or increased in the future, increased harvest of aspen stands and aging of older oak stands that weren’t harvested led to an increase in habitat quality relative to ForCAST scenarios with reduced harvest levels.

“One of the valuable things we can learn for wildlife research from the ForCAST model output is the relative impact of forest harvest level compared to the impact of climate change,” said Moen. “For black bears in Minnesota, climate change effects are predicted to have less of an effect on habitat suitability than forest harvest.”

The modeling is built off the well-known, but highly complex LANDIS-II, an open-source, forest change model developed over the past 30 years. LANDIS-II is a spatial temporal, tree species-level, cell-based forest model that simulates forest growth, succession, and disturbances over large landscapes and allows the developers to model forest change through time based on what we know about how forest changes through natural processes.

Forest Value

Understanding the value people place on our forests is important to decision-making. To quantify the value, NRRI Resource Economist Saleh Mamun conducted a “discrete choice” experiment to evaluate residents' willingness to pay for forest ecosystem services across 11 counties in northern Minnesota. What hypothetical amount of money would they be willing to pay for ecosystem services provided by forests? They were asked about their preferences for forest harvest, timber production, water quality, wildlife habitat and carbon sequestration.

“We learned that people value some increase in timber production – just 10 percent – but increasing timber production a lot shifts their preference toward other forest-based ecosystem services, like wildlife habitat and recreational use,” explained Mamun.

The Natural Resources Research Institute’s mission is to deliver integrated research solutions that value our resources, environment and economy for a sustainable and resilient future.