Those algal communities are signaling possible changes to come. To better understand the trajectory of stressors on this vast freshwater resource, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency upped its funding for ongoing NRRI research.

The five year grant of $2.5 million will continue monitoring of freshwater algae – an effort underway for the past decade. But the research will expand to gathering data in the near-shore areas of the Great Lakes and deploying robots to collect data year-round, including under the ice in winter.

“Because of the discoveries we’ve made so far and the incredible food web impacts, this is a natural progression for the research,” explained Euan Reavie, NRRI senior researcher and program lead. “We need more thoroughly collected data to make predictions about where things are going, especially with climate change impacts.”

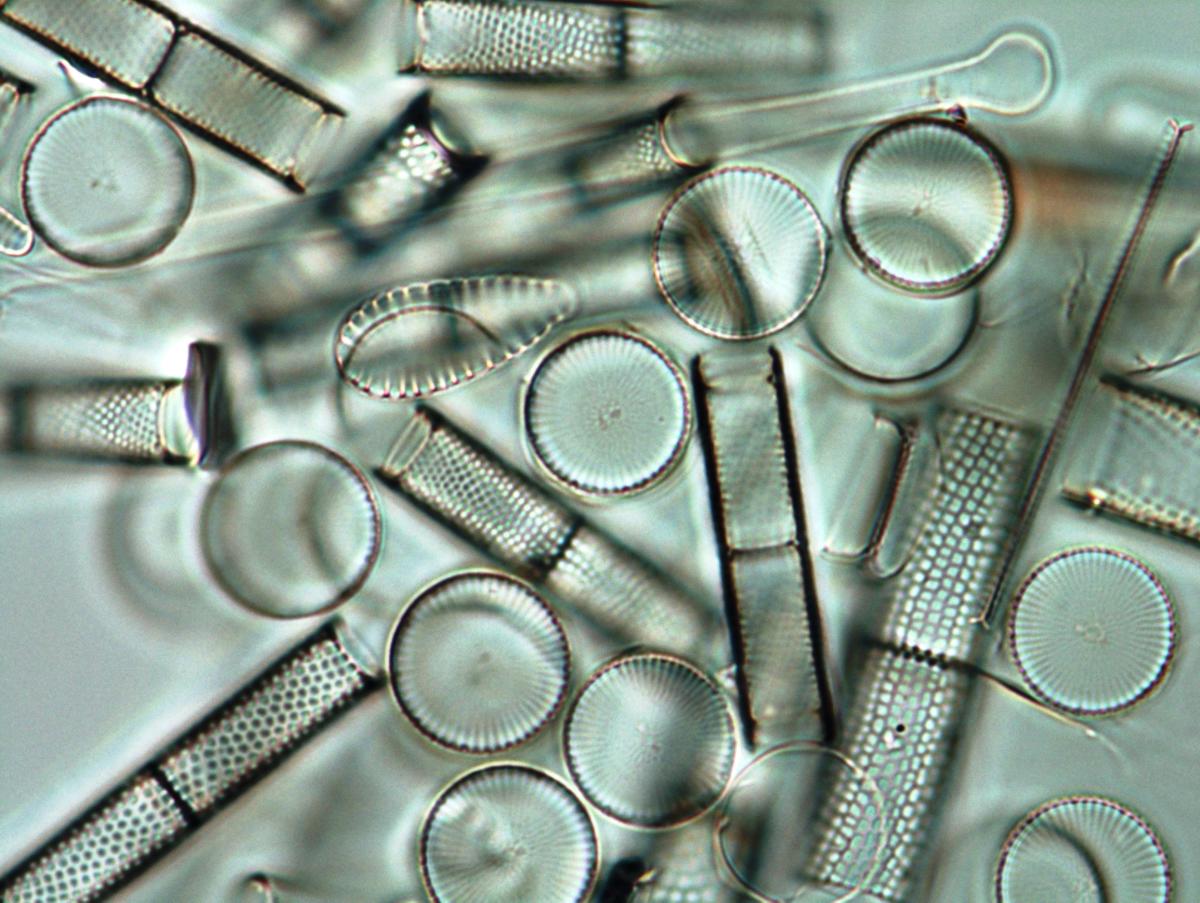

Over the past 10 years, Reavie and his team have documented historical Great Lakes water quality changes going back 200 years using algae fossils in sediment as indicators of change. This has given the scientists an understanding of the long-term impacts of nutrient overloads, invasive species, climate change – especially accelerated in the recent 30 to 40 years – as well as positive impacts of remediation efforts. All of these things are happening, and the evidence shows profound effects on the base of the food web. The study will include predictions for future impacts based on the historical data.

Deploying year-round, robotic sampling technologies will gather data that have been previously unavailable to scientists. Two submerged buoys with remote sampling devices will be stationed in each of the lakes to collect and preserve phytoplankton samples and store them until retrieved a full year later.

“The winter food web is probably pretty important, but we’ve never been able to get under the ice to collect samples,” said Reavie. “What species are ‘winter’ species? What happens before spring thaw to set up changes for the next season? Right now, we just don’t know.”

Another expansion of research will take place with several new sampling locations in shallower, nearshore regions of each lake. These nearshore data will be closer to the stress associated with human activities on the land, and may tell a story that more directly reflects human-Great Lakes interactions. The scientists expect the nearshore and offshore samples to tell unique, but related stories about lake conditions.

“This is exciting because the tiny species we see from 200 years ago are completely different than what we see today,” Reavie said. “They keep changing because of human activities. If you care about cold water fisheries, you should really care about what’s happening at the bottom of the food web.”