With one million named species of insects – and about four million more as yet unnamed – it’s easy to understand why there’s still a lot to learn about these little critters. But it’s their abundance that also makes it very important to understand their impact in our world -- and how that impact may be changing.

But gathering that data isn’t easy. Scientists use radio collars to track Canada lynx movements. They attach bracelets to bird legs. They monitor trail camera photos. For obvious reasons, these techniques won’t work with insects.

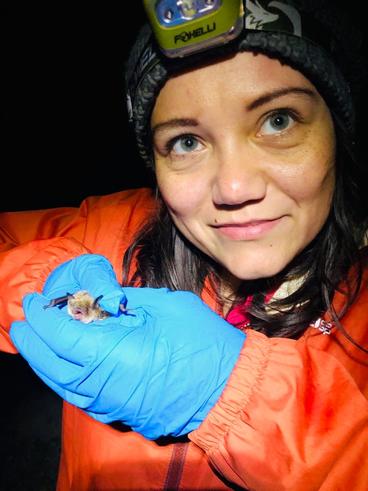

So Miranda Galey found an interesting way to learn more about insects: bat poop.

As a master’s degree student at UMD and a NRRI researcher, Galey started thinking about what she could learn from the bat guano (feces) samples that had been collected during NRRI’s bat research project. We know bats eat insects, but which ones? Do they eat invasive forest pests? And do the seven different bat species in Minnesota eat different insects to share the resources?

“It’s really important to understand bats’ impact on the insects and the forests since some species are declining sharply in Minnesota,” said Galey. “Insects are just really hard to study because there are so many species and they can look so similar.”

So she turned to Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis of bat guano. It resulted in Galey’s Master’s thesis, “Predator to Prey to Poop: Bats as Microbial Hosts and Insectivorous Hunters,” which she defended in late August.

DNA contains the biological “instructions” for each species. After Galey prepared samples, gene amplification and sequencing was done at the University of Minnesota Genomics Center. She then identified the insects by cross referencing the sequences with the Barcode of Life Database which has about 6 million DNA barcode sequences from some 550,000 species. This allowed her to map which insects and how many were consumed by Minnesota bats.

The results? From the 360 fecal pellet samples collected, bats ate 17 species of mosquitos, five of which can spread diseases to humans. And the Northern Long-Eared bats were the most voracious mosquito consumers. Minnesota bats also ate about 25 species of invasive forest pests, like the spruce bud worm, pitch-eating weevil, and saddlebacked looper. The study also identified nine pest species that had not been previously recorded in Minnesota.

“Overall, the bats I studied ate 535 different species of insects, including some non-flying arthropods like spiders,” said Galey. “This technique is really exciting because fecal samples are collected during the course of research from many bat species and we’re just uncovering what they can tell us.”

Of particular interest to Galey is understanding how insect species might be changing and rearranging as they face climate change scenarios. With baseline data on the distribution of insects across the state, Galey is interested in continued monitoring to understand how insects react to warming temperatures in the environment. Another part of her master’s thesis research analyzed the microbiome of bat intestines to better understand how they work.

Galey’s co-advisors for this work were NRRI Senior Scientist Ron Moen and Assistant Professor Jessica Sieber in UMD’s Department of Biology. NRRI’s bat research was funded by Minnesota’s Environmental and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources.