One of the fun things about discovering a new species is naming it. By that measure, Euan Reavie and his team have had a lot of fun.

They’ve discovered 28 diatom algae species in the coastal Great Lakes, previously undocumented. They gave them names like Navicula (the genus) wisconsinensis (because they found it on Wisconsin coastlines). Or Pantocsekiella laurentiana (because of its dominance thoughout the Laurentian Great Lakes). Or Navicula concertina (latin for “small accordion,” which the diatom resembles).

“It’s better than giving them a number which doesn’t tell you anything about what it is,” said Reavie, NRRI senior scientist and author of a new book on diatoms, published in August by Koeltz Botanical Books. The title doesn’t leave a clue to its popularity – it’s already sold out and a second press is underway – Diatom Monographs, Monoraphid and Naviculoid diatoms from the Coastal Laurentian Great Lakes.

“As soon as it’s published, books like this are purchased by libraries and taxonomic museums,” Reavie said. “We use these books in our lab, sitting open next to our microscopes. Anyone in the field of freshwater algae and diatoms all over the world will want one.”

Diatom algae make up much of the base of the Great Lakes food chain. They’re foundational to the whole freshwater ecosystem. And Reavie estimates – no one knows for sure – that there are millions of different species. The reason for the mind-blowing biodiversity is that the Great Lakes offers many different niches that diatoms have evolved to fill.

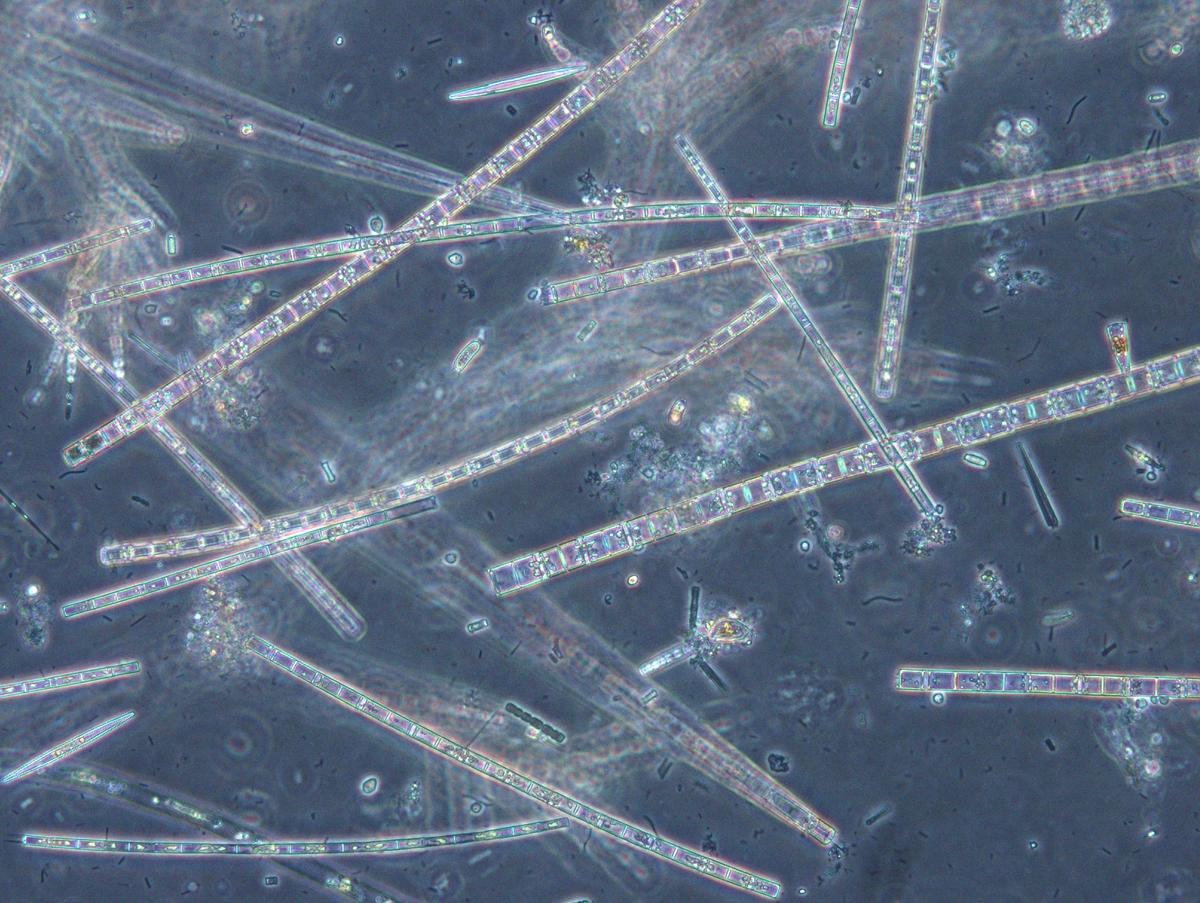

It’s really important to Reavie and other freshwater diatom scientists to be able to identify the different species because it helps them understand what’s happening in water resources. A salt tolerant diatom in freshwater lakes, for instance, might indicate road salt is getting into the lake. Or a warm water diatom in cold Lake Superior might indicate warming temperatures. And using paleolimnology, Reavie and his team can look at the diatom fossils in sediment cores going back hundreds of years to understand changes in water quality over time.

“While pure science -- like describing species -- is important, we always have an eye for the applied sciences. We want to know what these species mean, ecologically,” said Reavie. “If a stakeholder or agency needs environmental information and we have an assemblage that’s hard to describe, that’s frustrating.”

For each species in the book, including the 28 new species (and some 100 potentially new), Reavie describes the diatom with photos. And based on where and under what conditions each species was found, ecological details are also described. The 207 samples came largely from NRRI’s past Great Lakes Environmental Indicators project which ran from 2002 – 2010, which was funded by the Environmental Protection Agency.

“In the Great Lakes coastal zones, diversity of diatoms is so high that we could only document a subgroup for now,” Reavie said. “If we wanted to publish a book on all the species, it would take more than my lifetime and would go floor to ceiling.”

The book can be purchased from the publisher online.

Photo above: Microscope image of a mixture of mostly filamentous diatoms collected from Duluth-Superior Harbor.