In the cells of all living things – you, me, eagles, cockroaches –DNA holds the unique biological “instructions” that make us who and what we are.

That’s an important job. But today, new technologies help us tell more of DNA’s story. Sequencing the DNA (basically, determining the order of the chemical building blocks) for thousands of species – with more added every day – allows scientists to use this information to save research time and money.

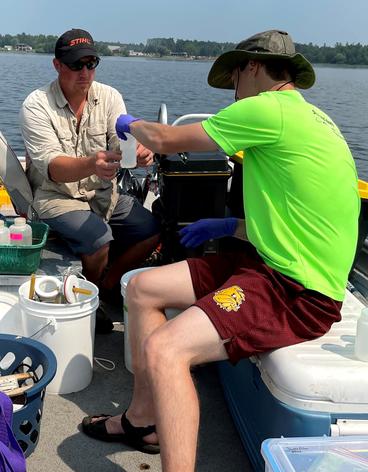

In the case of NRRI Aquatic Ecologist Josh Dumke, DNA left behind by invasive species in lake environments can help identify the presence and extent of invasive species spread in Minnesota lakes. Dumke estimates that using this “environmental DNA” or eDNA can increase the scope of lake monitoring because they can search for many species from each water sample.

“Throughout a species’ lifecycle, they’ll throw off DNA into the environment,” explained Dumke. “For example, their feces or skin fragments or exoskeletons all have DNA we can collect.”

The scientists capture the eDNA by filtering water samples and then run a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique to amplify, or copy, the DNA sequences.

But first, they need to figure out how to optimize the process to capture the most eDNA each time. That’s the focus of their work this year. How much water should they collect? What type of filter works best in the lab? What time of year is best to capture the most variety of species’ DNA? How long does DNA survive in the environment? What combinations of all methods works best?

They’re also taking extra care to make sure the samples from lake-to-lake are not cross contaminating.

One of the greatest benefits to using eDNA is that water samples can be collected by staff or volunteers with relatively little training. And while this early warning – a positive DNA ‘hit’ is detected –shows general locations of aquatic invasives, a trained human will still need to go out and confirm its presence and abundance, but much more efficiently.

“I expect that when we know which combination of methods optimize the use of eDNA monitoring for multiple aquatic invasive species, it will actually become more cost effective than traditional surveys,” said Dumke. “This means more lakes could be visited and monitored with the same amount of money.”

In addition to Pike Lake, NRRI’s experimental sampling efforts are taking place this summer on Lakes Vermilion, Shagawa, Lake of the Woods and the St. Louis River Estuary.

Funding for this project was provided by the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center (MAISRC) and the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR).

TOP PHOTO: Anna Totsch hands off a water sample to Collin Krochalk.